It was just another beautiful morning in paradise in Hawaii on January 13th, 2018.

Tourists flowed to and from the airport, locals picked up breakfast, while others spent their Saturday morning at home.

But the hustle and bustle of island life ground to a halt at 8:07 AM, when everyone’s phone began dinging, beeping, and buzzing.

Some assumed it was a weather alert, yet the skies were clear.

But when people began reading their notifications, panic set in: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

Some called loved ones, others wandered in disbelief.

Desperate eyes scanned the skies for signs of an attack. Still, only the wild blue yonder stared back. A minute went by, then ten minutes. Then, twenty minutes. No missiles, no mushroom clouds, no shockwaves.

Nothing.

Finally, after 38 minutes of despair and confusion, a second notification came in, saying it was a false alarm.

We get people make mistakes. The pizza guy forgets your drinks, a paycheck is delayed, or a rubbernecking driver rear-ends you on the way to work.

But accidentally sending a mass notification declaring there is an immediate missile threat, and adding that ‘this is not a drill?’

How does that happen? It’s hard to even accidentally delete a Word document these days.

In the aftermath, some questioned not only the process but also whether the government should have the ability to cause such pandemonium so easily.

While many people in Hawaii suspected the notifications were erroneous because not all alarm mechanisms, through radio, TV, and outdoor sirens, were activated, what would happen in the face of a real, imminent mass casualty event, such as a meteor or alien invasion?

Would warning the public do more harm than good? Do we have the right to be informed?

Grab your bug-out bags, and let’s hunker down to find out.

Argument: People DO Have a Right to Know!

Freedom is the right to tell people what they do not want to hear. -George Orwell

Main Points

Informed Decision-Making

Public Accountability and Trust in Governance

Collective Action and Survival

Moral Right to Truth

Point #1: Informed Decision-Making

People have a right to make informed decisions about handling catastrophic events, whether it's traveling closer to loved ones or securing survival resources.

During the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor event, people were left unprepared for the shockwave that injured over 1,500 people. Had experts caught the threat and heeded the warning, perhaps injuries could have been mitigated, such as by staying away from windows or getting off the roadways.

Point #2: Public Accountability and Trust in Governance

Governments and institutions have a duty to be transparent in severe impact situations.

When people know the government is hiding risks, such as the 1947 Roswell incident, it erodes public trust and spawns countless conspiracy theories.

In 2020, when the Pentagon released a new UFO video captured by US fighter pilots, it stirred public demand for the truth around extraterrestrial life, as people argued that we expect the government to share what they know.

Point #3: Collective Action and Survival

When we know about imminent threats, people can collectively mitigate harm or survive such events by coordinating evacuations, sharing resources, or building shelters.

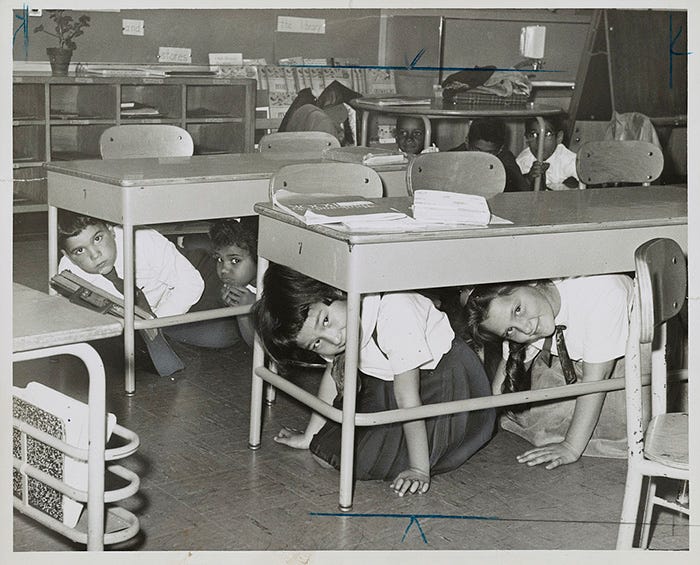

During the Cold War, public knowledge of nuclear risks led to civil defense programs such as Duck and Cover, which allowed people to take up a sense of responsibility. However ineffective that strategy might have been.

In the case of an alien invasion, civilians could assist the military, as we saw in the 1996 film Independence Day, where scientists weighed in on potential solutions.

Point #4: Moral Right to Truth

Humans have a moral duty to inform each other in the face of a cataclysmic event to allow for closure, spiritual reflection, or time to spend with loved ones. Secrecy denies all this.

In 1998, when NASA announced the potential 1997-XF11 asteroid impact, it sparked public debate with many people wanting to engage with such information, although the threat was later downgraded.

Rebuttal: People DO NOT Have a Right to Know!

I've always thought that when they say ignorance is bliss, the converse to that is that knowledge is hell. The more you know, the bleaker things can get. -Terence Winter

Main Points

Preventing Panic and Societal Collapse

National Security and Strategic Response

Uncertainty and Misinformation Risks

Paternalistic Duty to Protect

Point #1: Preventing Panic and Societal Collapse

Some people might work together to mitigate risk in such an event, but most people will only look out for themselves. If the government were to announce an imminent invasion or mass casualty event, it could trigger looting, violence, and infrastructure breakdown.

When information is limited to key personnel, they can manage the threat without bedlam.

In 1938, during Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds radio broadcast, which depicted a fictional alien invasion, many people panicked. A real-world event with modern communication could exponentially amplify chaos.

Point #2: National Security and Strategic Response

A mass casualty event announcement could give adversarial nations an opportunity to compromise military or scientific efforts, or information exploitation.

During the 1960s U-2 spy plane program, secrecy about unidentified aerial phenomena was maintained to protect national security, even if it led to UFO speculation.

If public pressure forces quick, uncoordinated actions, early incoming meteor disclosure might hinder international cooperation, such as with NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), designed to redirect asteroids by crashing spacecraft into them.

Point #3: Uncertainty and Misinformation Risks

While technology has vastly improved, early meteor or alien detection can be wrong, and sharing bad info could undermine government credibility, as we saw in the 2018 false missile alert.

In 2004, initial reports of asteroid 2004 MN4 (Apophis) suggested a 2.7% chance of Earth impact in 2029. NASA delayed public announcements until refining the risk to near-zero to avoid panic. Many people were glad they didn’t know.

Point #4: Paternalistic Duty to Protect

People don’t always process uncertain circumstances calmly. Given a potential end-of-the-world scenario, why cause mass public distress?

Whether there is a chance of survival or not, the overall social welfare is more important than adhering to a perceived “right to be informed.”

In the 1998 film Deep Impact, the US government keeps the incoming comet’s trajectory a secret to prepare shelters, much in the same way mom or dad might keep the kids ignorant during an incoming tornado or a loose serial killer.

Are We Asking The Right Questions?

Just a few weeks ago, on April 28, parts of Spain, Portugal, and France experienced a widespread power outage lasting for about ten hours. Most people’s minds went to cyber attacks, but they quickly ruled out that scenario and human error.

While many turned the debate to renewable energy faults, others took to the airwaves to blame solar flares, similar to what happened in the May 2024 Solar Storms that impacted power grids and GPS systems.

In these cases, it makes sense for civilian infrastructure to get a heads up, as many power companies minimized output to mitigate danger.

But generally, do people have a right to someone else’s labor? That depends on whether our tax dollars are part of the equation.

Of course, we don’t have a ton of alien invasions or asteroid encounters to make the best estimate, so it seems public disclosure depends on the circumstances.

Maybe the better question is, do you want to know?

We don’t need Bruce Willis on an asteroid or aliens chasing Will Smith in a fighter jet to understand how people will react in the face of a global threat.

Disasters such as California wildfires, New Orleans hurricanes, or Midwestern tornadoes happen relatively frequently. While hardly a global event, it does turn localized worlds upside down.

Yet many people don’t bother preparing the basics, such as stocking non-perishable foods, flashlights, or batteries.

Just look at 2020, did people work together? Or did they buy all the toilet paper and charge people $100 a roll in the Walmart parking lot?

Are people afraid of being called “preppers?” Or does preparing mean shattering the facade that life on Earth might not always be Starbucks, manicured lawns, and Amazon same-day delivery?

What do you think? Do people have the right to be informed in dire circumstances? Or does it depend on the situation?

Maybe the best bet is to take the Boy Scout route and be prepared.

Meme of the Week

Brand of the Week: Meadow and Fern

Meadow & Fern, founded by parents seeking safer cleaning solutions, creates plant-powered, non-toxic household products like dish soap, laundry detergent, and stain removers.

Using renewable, biodegradable ingredients, their hypoallergenic formulas are free of harmful chemicals, ensuring a healthy home.

Produced in small batches in the USA, they offer a 100% Happiness Guarantee, promising effective, eco-friendly cleaning with a fresh, worry-free feel.

Head to Meadow and Fern and take advantage of the Mother’s Day Sale!

American of the Week: US Army Staff Sergeant Robert J Miller

On January 25th, 2008, Staff Sergeant Robert J. Miller and his team were conducting a reconnaissance patrol in Gowardesh Valley, Afghanistan.

After spotting and initiating an attack with his vehicle’s grenade launcher, his team relayed detailed information to command to begin close air support.

When the enemy launched a counter-attack, Robert, as point man, charged the enemy multiple times to allow his team to maneuver by drawing attention to himself.

Despite taking a round to the upper torso, Robert continued, killing at least 10 enemy fighters and wounding many more.

Sadly, the shot Robert took would eventually kill him. For his bravery and selfless service, Robert was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Stephen left behind his parents, Philip and Maureen Miller, his brothers, Thomas, Martin, and Edward, and his sisters, Joanna, Mary, Therese, and Patricia. Remember Robert today.